Grounded Theory: Generating evidence for practice and delivery of care

Author

Geraldine Foley BSc.OT, MSc, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Email: foleyg3@tcd.ie

Abstract

Qualitative research methods as for quantitative research methods generate evidence for practice. Grounded Theory (GT) is a qualitative approach to doing research. This short communication briefly explains GT and outlines the value of GT for practice. Key methodological features of GT and considerations for appraising a GT study are outlined.

Key words: Grounded theory, Evidence, Best Practice, Theoretical Frameworks, Intervention

Introduction

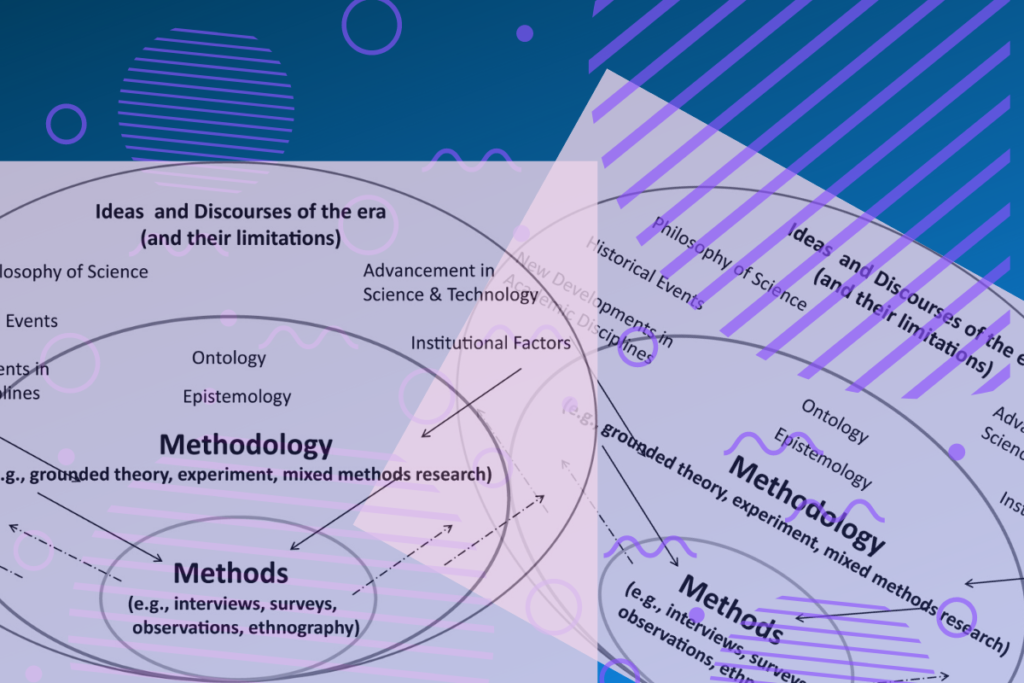

Methodologists have traditionally adopted polarised ontological positions between qualitative and quantitative methodologies and situated qualitative methodologies primarily within the relativist and constructivist paradigms (Cruickshank, 2012; Giacomini, 2001). However, in real terms, qualitative research incorporates both constructivism and realism (Clark et al., 2005). In healthcare, qualitative researchers typically focus on subjective experiences in practice, but they do so in the knowledge that structure and contexts shape experiences and outcomes in practice. Grounded Theory (GT) is a commonly used qualitative method that ‘grounds’ the human perspective in data and contextualises the human perspective in order to explain phenomena in or for practice.

What is Grounded Theory (GT)?

GT is a pragmatic, systematic approach to doing research – essentially a set of techniques and procedures used to build concepts and theory from data (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). It is also the product of the research i.e. theory that is grounded in data. GT is primarily inductive which means moving from the specific to the general in order to explain phenomena and build theory. However, GT is also abductive and deductive because inferences are made between data to generate theory and explain data (Bryant, 2017; Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015). Central to GT is the emphasis on ‘process’ which means how people inter/act in response to context (i.e. events, situations or circumstances), and the consequences of these inter/actions. GT is very much focused on the complex interrelationships between conditions (micro to macro), the inter/actions and behaviours which they can give rise to, and the consequences arising from inter/actions and behaviours in practice. GT researchers typically seek to understand the range of possible conditions and consequences in a study related to practice.

Sampling in GT

A distinctive feature of GT is theoretical sampling (Butler et al., 2018; Conlon et al., 2020). Data collection and analysis in GT intertwine, and ongoing comparison between data steers the course of inquiry. In GT, the researcher must move from purposive sampling (e.g., sampling for heterogeneity along standard dimensions of the population(s) under study) or any other form of non-probability sampling, to sampling participants and/or other sources based on emerging concepts in the data i.e. theoretical sampling. In other words, the developing concepts are used to guide where, how and from whom more data should be collected.

Data collection in GT

GT can incorporate multiple forms of data collection including for example, individual interviews, focus groups, observation, field notes, documentaries, archival resources, or other written or multimedia resources. Interview guides for interviews and focus groups in GT studies tend to be lightly or semi-structured at the outset to generate data inductively. As GT studies progress, questioning becomes more focused in order to expand on emergent findings and build relationships between concepts in the pursuit of theory (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). GT-based interviewing typically incorporates a mixture of open-ended, probing, and clarifying questions needed to fully expand on emergent concepts. Field notes in GT function primarily as a record during data collection to help contextualise the data. Observational data can be used effectively to provide further insight into key events and behaviours that are grounded in the data. The above forms of data are used in other qualitative approaches, but it is GT’s orientation towards ‘processes’ (i.e. generating data on inter/action in response to context) that distinguishes their use in GT (Timonen et al., 2018).

Data analysis in GT

Analysis in GT differs somewhat to how data is analysed in other qualitative approaches. Although most qualitative approaches involve coding for and labelling concepts, they don’t fundamentally involve theorisation of data. In GT, constantly comparing data with data through iteratively-linked stages of coding, the researcher first ‘opens up’ the data (open coding) to identify and label key incidents, situations, behaviours and patterns in the data, and then looks for tentative relationships between these concepts (axial coding) in an attempt to build concepts and generate theory. The final stage of analysis in GT known as ‘selective’ or ‘theoretical’ coding, involves identification of a core category (most encompassing concept) and explanation of how the core category can be explained by all other key categories that make up the conceptual framework or theory (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). The core category represents the overarching explanation for the phenomenon under study and is the main concept that all other concepts relate to. Analysis in GT is aided by conceptual diagrams that map out developing conceptual frameworks or theory (Kennedy-Lewis, 2014) and by theoretical memos (Montgomery & Bailey, 2007) which document the methodological steps taken by the researcher including how the researcher identified relationships between concepts to build a conceptual framework or theory.

Theoretical saturation

The goal of a GT study is to reach theoretical saturation of the data. Saturation in GT is distinctly different from saturation that is signalled simply by the absence of new data. Rather, saturation in GT occurs when no new conceptual or theoretically driven insights emerge from the data that can further build and explain key concepts in the data (Saunders et al., 2018). ‘Saturated’ data in GT means that data have been heavily contextualised and so therefore capture the complexity of processes in practice.

What does GT offer practice?

GT can explain phenomena for practice

The purpose of any GT study is to provide an explanation about the phenomenon under study – the primary function of GT is to explain. For example, randomised-controlled trials may provide promising results for the effectiveness of interdisciplinary-led self-care programmes for the management of osteopenia in older adults. However, evidence may also point to low levels of engagement by older adults with osteopenia in self-care programmes despite the proven positive effects of such programmes. Understanding how and why older adults with osteopenia engage (or not) in self-care programmes, including the conditions (e.g., accessibility of programme) that might facilitate or limit their participation and the consequences (e.g., level of adherence to prescribed therapeutic regimen) of participation or non-participation, could be illuminated by GT. The end-product of GT investigation here would be a fully conceptualised and well-contextualised theoretical framework that could explain why older adults with osteopenia engage or don’t engage with such programmes. The knowledge gained from the GT study could then guide healthcare professionals on how to deliver care that would be sufficiently sensitive to the key contexts that influence patients’ participation in care and so optimise their outcomes through self-management of osteopenia.

GT can map out key processes in practice

GT is particularly useful when the basic parameters or key domains of an area of practice need to be mapped out. Here, GT can pinpoint key variables that may impact on practice and which further studies can then elaborate on. For example, a GT study that aims to explain how patients, family caregivers, and different healthcare professionals in palliative care navigate decision-making in relation to DNR (do not resuscitate), would not simply seek to capture patients’, family caregivers’, and healthcare professionals’ experiences of and preferences for care, or simply describe what DNR meant to individual participants. Rather, the GT study would set out to identify key patterns in participants’ decision-making including the key conditions (e.g., healthcare professional expertise, family support) that shape decision-making, and the key consequences of specific decisions surrounding DNR (e.g., initiation of assisted ventilation, admission to hospice care) in order to illuminate key variables (concepts) (e.g., burden of care) that underpin the decision-making process for DNR among patients, family caregivers, and healthcare professionals in palliative care.

How does GT shape practice?

GT can develop theoretical frameworks for practice

GT studies have developed an abundance of theoretical frameworks to explain processes in care including for example, service user discharge from care (Keogh et al., 2015), healthcare professional management of patient unexplained symptoms (Stone, 2014), adjustment trajectories in cancer (Matheson et al., 2016), and decision-making in end-of-life care (Romo et al., 2017). GT has also been used to develop frameworks for healthcare professionals that can improve care. For example, a GT study on how family caregivers in stroke become ready to assume caregiving duties in the transition from rehabilitation to home, generated a theoretical model on how to identify and bridge gaps for stroke caregivers’ readiness to care (Lutz et al., 2017). Similarly, a GT study of the experience of heart disease generated a framework for evaluating secondary heart disease programmes because it identified and explained key attitudes and behaviours that underpinned effective secondary prevention (Ononeze et al., 2009). Generation of explanatory frameworks and theory in GT is important for practice because explanations of key processes in practice, enable us as researchers and/or healthcare professionals to better understand how key events, incidents or actions/interactions can set the course for and/or explain outcomes in practice.

GT can aid development of interventions for practice

GT frameworks can be used to help develop interventions. For instance, a GT framework underpinning the development of a delirium prevention intervention has been used to establish the content and guide the implementation of a delirium prevention intervention (Godfrey et al., 2013) and aided in formulating a protocol for a randomised-controlled feasibility trial of the intervention (Young et al., 2015). GT can also explain how and why interventions work (or why they might not work) and to decipher what elements of an intervention may have helped improve outcomes. For example, a longitudinal GT study on how obese women engaged with a post-partem diet and exercise intervention (Bertz et al., 2015) found that sustainable weight loss was not achieved by the simple introduction of standard health behaviours but instead by the need to re-evaluate, persist with and accommodate to healthy eating and exercise behaviours. Essentially, GT can facilitate the implementation of best practice because it can identify conditions that give rise to better outcomes in practice (Sax et al., 2013).

How do we appraise GT evidence that is used to inform practice?

There are well-established guidelines for critically appraising qualitative research (e.g. Korstjens & Moser, 2018; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Mays & Pope, 2000). The following subsections outline how criteria for establishing rigour in qualitative research (credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability) (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) can be applied in GT.

Credibility in GT

Credibility refers to the truth of a qualitative study’s findings. In GT, credibility means the extent to which participant (or any other data) are rooted in the theory or explanations derived from the data. Member checking, a process in which participants are asked to verify what they have communicated is a common procedure to build credibility. In GT, researchers can choose to return to participants to validate concepts and theory and use prolonged contact with participants to further refine theory that has or is emerging from the data (Matheson et al., 2016). Prolonged contact with participants can also help to verify the stability and consistency of the GT findings overtime. A GT study’s credibility can also be aided by data triangulation (use of different sources of data in time, space and person) and constant comparison between different forms of and sources for GT data helps support the plausible explanations made from the data.

Dependability in GT

Dependability refers to the reliability of a qualitative study – whether the procedures of the study did in fact capture the phenomenon under investigation and the key processes that underpin it. In GT, a logical account of all steps taken (i.e. audit trail) should be sufficiently detailed so that the study could be replicated in different systemic contexts. Theoretical memoing during data generation together with transparent coding procedures increases dependability of a GT study because both coding and theoretical memos account for how the conceptual framework or theory has been generated from the data (Foley & Timonen, 2015). Negative cases or outliers can arise in GT as they do in other research methods but exceptions to key patterns in the data do not limit the dependability of a GT study. Rather, judgements about dependability in a GT study are made on how systematic comparisons have been made between data and the extent to which the categories or key concepts that make up the conceptual framework or theory are sufficiently ‘saturated’ to support the claims made from the data.

Transferability in GT

Transferability (also known as applicability) of a qualitative study refers to the usefulness of the findings. In GT, transferability is judged by the degree to which the analytical concepts or categories incorporate ‘every day’ or ‘real-life’ processes, including the tacit implications of these processes (Charmaz, 2014). Depth of and variation in GT concepts and categories are fully necessary for a GT study to have relevance to practice. Categories that have been ‘saturated’ and fully ‘dimensionalised’ means that the findings capture the complexity of processes and are therefore more likely to be applicable to practice. New insights and analytical categories gained from a GT study should also be substantial enough to refine current thinking in the field and to re-evaluate approaches to practice (Bryant, 2017). An expected outcome of any GT study is a clear distillation of how the findings can further inform research and practice.

Confirmability in GT

Confirmability refers to the degree to which the findings of a qualitative study could be reached by others. In GT, it must be clear how the conceptual framework or theory are clearly derived from the data even though it is the researcher who interprets the data and builds a conceptual framework from the data. In other words, the researcher must remain alert to generating findings from the data (i.e. not seek to extrapolate from data that is not part of the data) and at the same time remain ‘theoretically sensitive’ to the data (i.e. use insight and understanding of the topic to give meaning to the data) (Timonen et al., 2018). Confirmability of a GT study can be addressed by having more than one researcher code data and to cross check interpretation of key findings across the data. ‘Inter-coder reliability’ in GT research does not mean that researchers must have coded the data identically. Rather, inter-coder reliability involves discussion on different and similar interpretations of the data which ultimately converges on a shared interpretation and understanding of how data and theory have been generated. Detailed reflexive notes that document how the researcher’s own pre-conceived assumptions about the study has shaped all stages of data or theory generation are a useful tool to judge the confirmability of a GT study.

Conclusion

GT is very useful for practice because GT explains phenomena for practice and identifies key processes that underpin practice. GT can develop theoretical frameworks for practice and identify conditions and/or or actions/interactions that help explain outcomes in practice. Established guidelines for critically appraising qualitative research are easily applied to GT.

References

Bertz, F., Sparud-Lundin, C., & Winkvist, A. (2015). Transformative lifestyle change: key to sustainable weight loss among women in a post-partum diet and exercise intervention. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(4), 631-645. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12103

Bryant, A. (2017). Grounded theory and grounded theorizing. Pragmatism in research practice. Oxford University Press.

Butler, A. E., Copnell, B., & Hall, H. (2018). The development of theoretical sampling in practice. Collegian, 25(5), 561-566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.01.002

Charmaz, C. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

Clark, A. M., Whelan, H. K., Barbour, R., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2005). A realist study of the mechanisms of cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(4), 362-371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03601.x

Conlon, C., Timonen, V., Elliott O’Dare, C., O’Keeffe, S., & Foley, G. (2020). Confused about theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory studies. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 947-959. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319899139

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage.

Cruickshank, J. (2012). Positioning positivism, critical realism and social constructionism in the health sciences: a philosophical orientation. Nursing Inquiry, 19(1), 17-82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00558.x

Foley, G., & Timonen, V. (2015). Using grounded theory method to capture and analyze healthcare experiences. Health Services Research, 50(4), 1195-1210. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12275

Giacomini, M. K. (2001). The rocky road: qualitative research as evidence. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 6(1), 4-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebm.6.1.4

Godfrey, M., Smith, J., Green, J., Cheater, F., Inouye, S. K., & Young, J. B. (2013). Developing and implementing an integrated delirium prevention system of care: a theory driven, participatory research study. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 341. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-341

Kennedy-Lewis, B. (2014). Using diagrams to make meaning in grounded theory data collection and analysis. SAGE Research Methods Cases. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/978144627305014534926

Keogh, B., Callaghan, P., & Higgins, A. (2015). Managing preconceived expectations: mental health service users experiences of going home from hospital: a grounded theory study. Journal of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing, 22(9), 715-723.

Korstjens, I., & Moser, A. (2018). Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 120-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

Lutz, B. J., Young, M. E., Creasy, K. R., Martz, C., Eisenbrandt, L., Brunny, J. N., & Cook, C. (2017). Improving stroke caregiver readiness for transition from inpatient rehabilitation to home. Gerontologist, 57(5), 880-889. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw135

Matheson, L., Boulton, M., Lavender, V., Protheroe, A., Brand, S., Wanat, M., & Watson, E. (2016). Dismantling the present and future threats of testicular cancer: a grounded theory of positive and negative adjustment trajectories. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 10(1), 194-205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0466-7

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Qualitative research in healthcare. Assessing quality in qualitative research. British Medical Journal, 320(7226), 50-52. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50

Montgomery, P., & Bailey, P. H. (2007). Field notes and theoretical memos in grounded theory. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 29(1), 65-79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945906292557

Ononeze, V., Murphy, A. W., MacFarlane, A., Byrne, M., & Bradley, C. (2009). Expanding the value of qualitative theories of illness experience in clinical practice: a grounded theory of secondary heart disease prevention. Health Education Research, 24(3), 357-368. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn028

Romo, R. D., Allison, T. A., Smith, A. K., & Wallhagen, M. I. (2017). Sense of control in end-of-life decision making. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 65(3), e70-e75. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14711

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., … Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893-1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Sax, H., Clack, L., Touveneau, S., da Liberdade Jantarada, F., Pittet, D., & Zingg, W. (2013). Implementation of infection control best practice in intensive care units throughout Europe: a mixed-method evaluation study. Implementation Science, 8, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-24

Stone, L. (2014). Managing the consultation with patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a grounded theory study of supervisors and registrars in general practice. BMC Family Practice, 15, 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-014-0192-7

Timonen, V., Foley, G., & Conlon C. (2018). Challenges when using grounded theory: A pragmatic introduction to doing GT research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918758086

Young, J., Cheater, F., Collinson, M., Fletcher, M., Forster, A., Godfrey, M., … & Farrin, A. J. (2015). Prevention of delirium (POD) for older people in hospital: study protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility trial. Trials, 16, 340. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0847-2