Credit: Michael Helfenbein, Yale University

Authors and affiliations – see bottom of article

Introduction

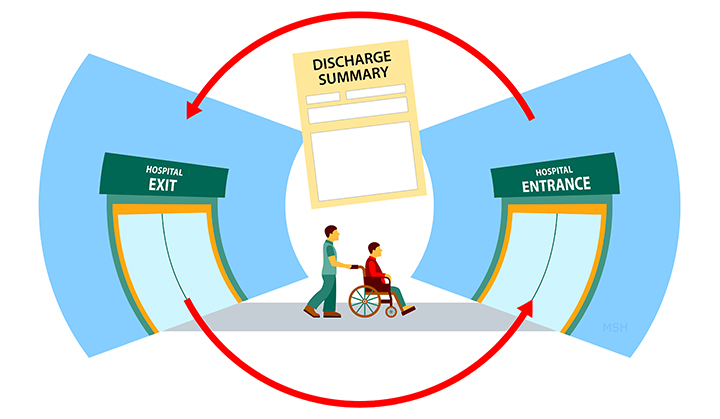

A major component of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s attempt to improve primary care practices has been care coordination post-hospital discharge (McDonald 2007, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014). The transition between the hospital discharge and resuming of care by the primary care physician (if the patient has one) is a vulnerable period. Often, home health care nurses that visit patients post-hospital discharge are asked to deliver care with absent discharge summaries, conflicting medication lists, insufficient information regarding wound care and drains, and an unknown status or presence of prior authorizations of discharge medications. When a question arises, home health care nurses find themselves with a hospitalist office that may defer to the primary care provider and a primary care provider that may not have even been notified of the hospital admission. In this paper, we suggest four concrete aspects of an ideal discharge summary based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s domains for improving care coordination for better interprofessional care of patients.

Background

Recently, a focus group study of home health care nurses (Jones 2017) described multiple transition challenges including determining who would take responsibility for home health care visit orders, figuring out how to access medical records from the discharging hospital, inquiring about wound care recommendations or plans for drains, and reconciling hospital discharge medication lists that do not resemble the primary care physician’s list. With patient safety and readmission rates being considered alongside length of stay and before-noon discharge rates, inpatient providers, outpatient providers, and home health care nurses must find ways to improve communication amongst each other.

Taking collaborative action on discharge

Below, we highlight four specific points of confusion resulting from calls from home health care nurses to our Family Medicine and Hospitalist practices and ways that inpatient providers can mitigate some of this confusion at the time of discharge. Each of these suggestions is linked to a domain of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (2014) Care Coordination Measurement Framework. We offer a joint perspective from an admission-discharge coordinator, inpatient nurse, outpatient physician, and inpatient physician in an attempt to build off of and respond to the home nursing suggestions for a safer transition.

Medication Management Part 1: Prior Authorizations

Our offices receive a high volume of post-discharge calls regarding unanticipated prior authorizations of medications prescribed at the time of discharge. Notably, the discharging provider may feel it is the responsibility of the outpatient provider to follow up, whereas, the outpatient provider may not have even known the patient was hospitalized, let alone understand the medication or care changes made.

Proposed solution: The discharge summary should include the phone number of the pharmacy at the discharging hospital within the discharge paperwork. This would allow access from the home health care nurse to the pharmacy and to the original prescriber (the inpatient provider) for immediate post-discharge follow-up,while not burdening the outpatient provider with care plan changes he/she may not be aware of.

Medication Management Part 2: Medication Reconciliation

Some models for discharge summaries include a “patient instructions” section where the physician can address reasons for medication changes in language understandable to the patient. However, for a provider coming to the home, there may be an additional layer of detail needed should the patient have a question about the medication or its purpose.

Proposed solution: The discharge summary should contain an abridged section at the end that serves as a written handoff between the discharging provider and the home health care nurse about specific goals or reasons for medication changes that cannot be easily gleaned from the full hospital course summary.

Establishing Accountability and Agreeing on Responsibility: Lines, Tubes, and Drains Follow-Up

Home health care nursing is often ordered by the inpatient provider due to lines, tubes, and drains placed either by a PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) team, interventional radiology, or surgery. While the timing of a central line removal may be obtained by looking at the antibiotic discharge date, home health care nurses may find it harder to know when and by whom drains such as Jackson-Pratt drains, nephrostomy tubes, etc may be removed or how to troubleshoot malfunctioning drains or if they need to be flushed.

Proposed solution: The discharge summary should contain a special section for lines, tubes, and drains and who the appropriate follow-up person should be. Additionally, if any drains or lines should be removed by the home nurse prior to a clinic visit (usually a PICC line), the timing should be clearly written in this section.

Assessing Patient Needs and Goals: Wound Care

As physicians in the hospital we may know the staging of a patient’s wound and have a general idea of the wound care being used based on orders recommended by the wound care team. However, the level of detail needed by home health care nurses far exceeds what is typically in the discharge summary (including the sequence of dressings and pictures of the wound at the time of discharge). Additionally, there is often no wound care clinic appointment provider post-discharge.

Proposed solution: The discharge summary should contain or link to the last wound care note when being printed out for the patient containing pictures, measurements, locations, and wound care instructions (including wound vacs).

Concluding comments

Improving interprofessional communication during the transition from hospital discharge to re-establishing care with an outpatient provider can have major effects on a vulnerable population. As discussed above, home health care nurses are instrumental in the transition but face significant obstacles that we, as inpatient and outpatient providers, nurses, and discharge coordinators, can address. The four above suggestions based on Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality domains for improving care coordination represent four concrete aspects of an ideal discharge summary from an inpatient provider’s end that can lead to better patient care coordination and interprofessional teamwork between the patients, the nurses, the inpatient providers, and the outpatient providers.

References

McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, Lewis R, Lin N, Kraft SA, McKinnon M, Paguntalan H, Owens DK. (2007). Closing the Quality Gap: a Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies. (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care and Quality.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2014). Care Coordination Measures Atlas Update. (Chapter 3). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research. Retrieved from: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/coordination/atlas2014/chapter3.html

Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, Bowles K, Lahoff D, Boxer RS, Masoudi FA, Coleman EA, Wald HL. (in press). “Connecting the Dots”: A Qualitative Study of Home Health Nurse Perspectives on Coordinating Care for Recently Discharged Patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Authors:

Michael McFall Jr

Section of Hospital Medicine, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Angela L. Nguyen

Penn Presbyterian Medical Center

Jenny Y. Wang MD

Department of Family Medicine & Community Health

Penn Presbyterian Medical Center

Flint Y. Wang

Section of Hospital Medicine, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Contact: flint.wang@uphs.upenn.edu