Below we provide the Abstract and a brief selection of this novel and exciting autoethnography that critically examines the if, why, where, and how of developing an interprofessional education (IPE) program from the ground up, told through text and comic art. The full story can be found here. The manuscript is true to the autoethnographic method(s), and explores related concepts, constructs, and debates associated with the lead author’s involvement with IPE as well as various facilitators and barriers associated with the ongoing processes. As discussed in the Methods section, the mix of comics and text not only provides a new lens to the audience, which may, in turn, foster relatability and more engagement with the material, but also showcases the collaborative enterprise that is graphic medicine. We hope you enjoy the selection below, and please feel free to contact the authors with any questions or thoughts.

Barret Michalec, PhD @BAMichalec

University of Delaware

Ian Sampson, MFA @ianesampson

University of Delaware

Author bios can be found after references.

ABSTRACT

The following is an autoethnographic case-story, told through text and comic book art, spotlighting the barriers and facilitators associated with building an IPE/IPP program within a specific institution. Part 1 of this story, shared here, focuses on: a.) providing personal background and cultural context for the emergence of the role of Associate Dean of Interprofessional Education, d.) the steps taken to centralize efforts and, c.) the reasoning behind the primary focus of integrating IPE within the undergraduate (i.e., college) level. This story spotlights various resources that were utilized in this initial process, discusses the achievements and macro-, meso-, and micro-level challenges thus far, and in turn, hopefully serves as a preliminary guide for other IPE innovators and leaders.

BRIEF SELECTION:

It is important to note however, that although the University does have a number of graduate-level health-related programs (e.g., exercise science, nursing, health services administration, health promotion, applied physiology, medical sciences, physical therapy, communications sciences and disorders, biomechanics and movement science, among others, with still more in development), it does not have a medical school (although we do have a large number of “premeds” at the undergraduate level). I believe this is a key facilitator to the development of IPE at this specific University given the status and related power differentials nested within and between the health professions, and, in turn, health professions education. Stated differently, the nested and often perpetuated (through formal and informal means) occupational status hierarchy that can trickle down into health professions education, can impact the development, implementation, and effectiveness of interprofessional education (Michalec et al., 2013; Bell, Michalec, & Arenson, 2014; Macmilan & Reeves, 2014) – but lacking such a program meant little “contaminating drippage.”

Another contextual issue that I consider a benefit to the development of IPE at the University is that I am not a healthcare provider. I am a sociologist that studies healthcare providers and health profession students. My research thus far had explored the socialization and professionalization processes nested within healthcare education, provider-patient interaction, and various structural and social-psychological aspects of healthcare delivery. My work crosses disciplinary boundaries, working on projects with various health care providers, and scholars from varying domains (psychology, education, policy, among others). Moreover, I have a background in IPE specifically, having worked with Thomas Jefferson University’s Jefferson Center for Interprofessional Education (JCIPE) evaluation sub-group since 2009. In other words, I had relevant background without the internal ties or alliances. But to be clear, regardless of my work in this specific field, my lack of clinical credentials made me somewhat distinct from most IPE scholars (i.e., researchers and program developers) who were/are of a clinical ilk being nurses, doctors, physical therapists, nutritionists, dentists, medical social workers, etc., or from an education background. Many other social scientists playing in this sandbox, even those who were working/appointed within clinical disciplines were using specific theories and concepts as flashlights to expose key barriers and facilitators to IPE and IPP or “gaps” in the IPE/IPP literature (e.g., Hean & Dickson, 2005; Baker et al., 2011; Kitto et al., 2011; Paradis & Whitehead, 2015; among others), but were not necessarily attempting to build IPE/IPP curriculum or programs themselves. This is not to say such scholars were not influencing or involved in IPE programs, but rather that it was unlikely that these types of scholars were/are spearheading comprehensive IPE development or the directors of IPE/IPP centers.

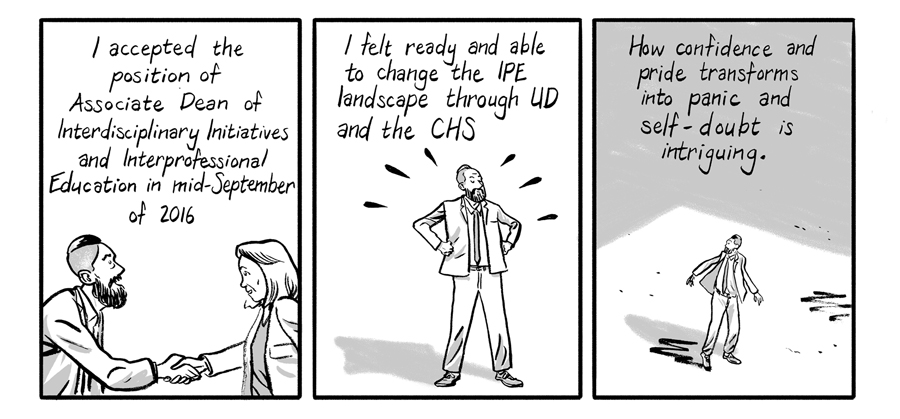

Moreover, this “other” perspective speaks to a larger contextual issue, how medical sociologists, and social scientists in general, are possibly perceived within the clinical realm. Link (2003), in his work, The Production of Understanding, highlights the “rule” of biomedical research and the related quieting of the sociological perspective in the clinical realm. He states, “And since much of the institutional power lies with the medical/biological perspective on mental and physical illnesses, the ideas of sociologists and other social scientists are at risk of being underappreciated” (458). This “institutional power” stems from the rise of authority and professional autonomy of medicine (Starr, 1982), and the perpetuated notion that clinical knowledge (acquired through health professions training, namely medical training) is the pinnacle of knowledge (Wear & Castellani, 2006), as well as the continued medicalization of behaviors (Conrad & Schnieder, 1981; Conrad, 2007). In turn, this biomedical focus not only impacts if and how we examine issues related to health and illness (i.e., micro, meso, macro-approaches), but also what aspects of health and illness are important to teach future healthcare professionals. If I was to take on this position, I would be an “infiltrator” of sorts, working within the clinical realm as an “other.” This opportunity was the primary driving force as to why I accepted the position – to have an impact on the healthcare workforce and healthcare delivery…..as a sociologist.

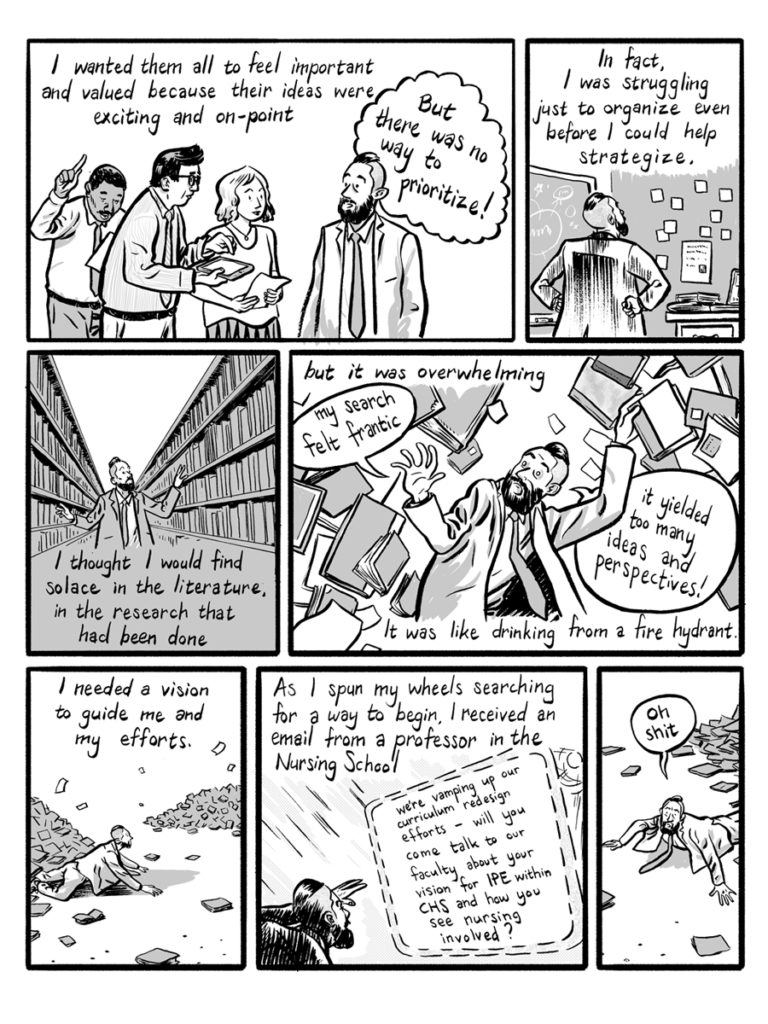

Although I felt well versed in all things IPE, I immediately floundered. There were so many starting lines. I didn’t know where to begin, and I was fraught with concern that my panic would not only be exposed, but be perceived as a lack of ability. I wanted to get a lay of the land regarding what interdisciplinary and IPE-based programs and courses were already on the books within CHS. I also wanted to read-up on how to create (and sustain) institutional change. I also needed to more thoroughly explore examples of IPE and IPP-based programs, curriculum, and initiatives from other institutions. There was so much already happening within the College in terms of curriculum and programming that could be perceived as “IPE-friendly” – meaning they had the fundamental ingredients to “qualify” as IPE learning opportunities but required enhancement and/or further integration. Plus, the College had a knack of moving quickly and, in turn, I was playing an incredibly difficult game of catch-up. To add to the fervor, there was already an excitement and knowledge-base regarding IPE among the CHS faculty and now they had someone to help them search out potential funding sources and opportunities, assist in designing evaluation and assessment protocols, and to help champion their programs in general.

But, as they say, “Necessity is the mother of invention.”

REFERENCES:

Baker, L., Egan-Lee, E., Martimianakis, M., & Reeves, S. 2011. Relationships of Power: Implications for Interprofessional Education. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 25: 98-104.

Bell, B., Michalec, B., & Arenson, C. 2014. The (Stalled) Progress of Interprofessional Collaboration: The Role of Gender. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 28(2): 98-102.

Conrad, P. 2007. The Medicalization of Society. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Conrad, P., & Schneider, J. 1981. Deviance and Medicalization: From Badness to Sickness. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Hean, S. & Dickinson, C. 2005. The Contact Hypothesis: An Exploration of its Further Potential in Interprofessional Education. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 19: 480-491

Kitto, S., Chesters, J., Thistlethwaite, J., & Reeves, S. 2011. Sociology of Interprofessional Health Care Practice: Critical Reflections and Concrete Solutions. UK: Nova Science Publishers.

Link, B. 2003. The Production of Understanding. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 44(4): 457-469.

MacMillan, K., & Reeves, S. 2014. Editorial: Interprofessional Education and Collaboration: The Need for a Socio-Historical Framing. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 28(2): 89-91.

Michalec, B., Giordano, C., Arenson, C., Antony, R., & Rose, M. 2013. Dissecting First-Year Students’ Perceptions of Health Profession Groups: Potential Barriers to Interprofessional Education. Journal of Allied Health. 42(4): 202-213.

Paradis, E., & Whitehead, C. 2015. Louder Than Words: Power and Conflict in Interprofessional Education Articles, 1954-2013. Medical Education. 49(4): 399-407.

Wear, D., & Castellani, B. 2000. The Development of Professionalism: Curriculum Matters. Academic Medicine. 75(6): 602-611.

Starr, P. 1982. The Social Transformation of American Medicine.

Author Bios:

Barret Michalec is the Associate Dean of Interprofessional Education and Interdisciplinary Initiatives, and an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Delaware. His research explores socialization and professionalization processes within health professions education.

Ian Sampson is an artist and educator working to reconsider social narrative constructions. His comics and prints probe the relationship between memory, history, and fiction, and how that intersection shapes our vision and futures.